Originally appeared in Eclectica Magazine.

On the dusty streets at the north end of Pokhara, Nepal, my wife, Sonia, and I were darting in and out of concrete storefronts, scrambling for last-minute supplies. It was Oct. 6, 2014, according to Western calendars, and we were a day behind schedule for our Himalayan trek. Outside a bakery, as motorcycles dodged familiar potholes, I turned and was nearly sideswiped by a dead body. Several boys in white shirts and black pants with white flags were marching down the street, trailed by young men carrying a small woman wrapped in ornate red linen on a gurney. She was on her way to the cremation ceremony. It was our first sign that death was hovering around us, mere feet away.

We were heading out on the 128-mile Annapurna Circuit, long considered the greatest trek in the world, as it circumnavigates the 26,545-foot Annapurna massif in a roughly horseshoe shape and connects village to village, accented by Hindu and Buddhist culture. We'd also tacked on a second leg to the journey, a side trip to Annapurna Base Camp/Sanctuary, bringing our total distance closer to 200 miles. Because we were scheduled to be out for 25 days, we were in a state of panic trying to second guess ourselves. What had we forgotten?

A deadly tropical cyclone, meanwhile, was spawning in the northern Indian Ocean, and we were oblivious to it and anything else beyond our own disorganization. We were among throngs of tourists heading deep into the Himalayas, the Sanskrit word for "abode of the snow." It wasn't supposed to be extreme mountaineering, but overnight it would morph into one of the worst trekking disasters.

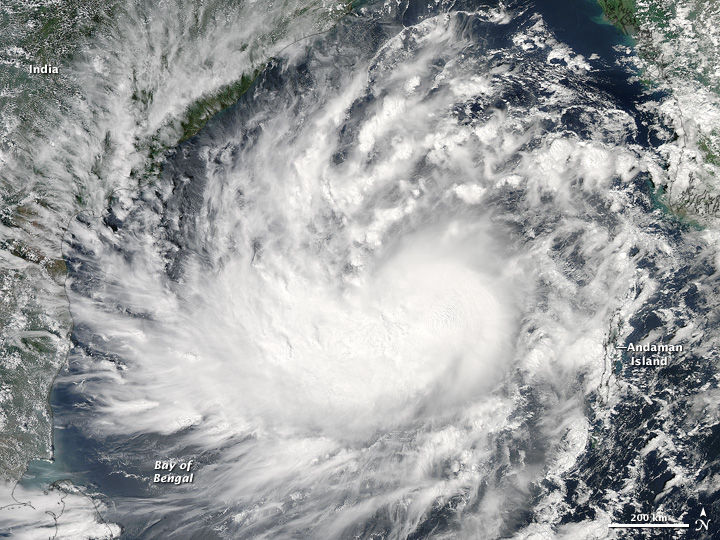

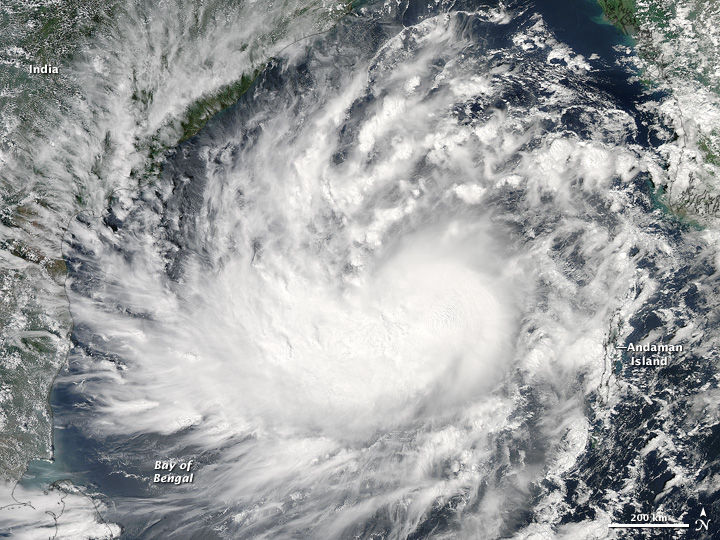

As I would learn later, Cyclone Hudhud began as a line of thunderstorms in the northern Indian Ocean. NASA's Aqua space satellite captured a set of infrared data that looked more like a tie-dyed T-shirt. On Oct. 8, an eye was becoming visible to forecasters. With winds exceeding 131 mph, it moved from east to west across the Bay of Bengal and reached Category 4 status shortly before making landfall. By then it was fully developed, and its puffy clouds looked like an exploded snowball. This had set off a controlled panic in India where more than 700,000 people were forced to evacuate the coasts. The first confirmed casualty, according to media reports, may have been a 9-year-old girl who died in a rescue boat accident.

As Hudhud scraped across land, the storm's remnants headed for the Himalayas, creating an entirely new kind of danger as the mightiest of precipices obstructed its path and converted rain to snow. There was little reaction in Nepal. The country was distracted with preparations for its post-monsoon season festivals, and it was high season for tourists when clear weather provides some of the best views of 8,000-meter peaks.

Lowlands

We'd hired a 25-year-old guide, Yashoda Baniya from 3 Sisters Adventure Trekking. The company was a pioneer in training young women to work away from home, a radical concept when three Nepali sisters teamed up and started the business back in 1994. Their guides go through extensive training and a selection process. Not quite five feet tall, Yashoda made her presence known through physical toughness and a sunny disposition. She could find almost anything humorous. But she was in a state of shock the next morning when she saw us near the bus that was to carry us to the trailhead. Sonia had a cold and, in a silly bout of confusion with foreign bottles, I'd swallowed a large quantity of hydrogen peroxide late the previous night. My throat was burning and my voice nearly gone. In addition to leaving later than expected, things weren't starting off well for a couple from Colorado.

The bus ride was typical of a developing country: dangerous and overcrowded with high-pitched Indian and Nepali music filling what little hot space was left. Despite some passengers having to sit on wicker stools in the aisle, spirits were running high, but there was a tinge of apprehension. Little did we know this old hunk of metal hurtling down the back-broken roads marked the beginning of something greater. Each cluster of trekkers forms an international tribe as they leapfrog their way up the trail. Those who'd left on the bus the previous day, which was supposed to include us, would feel the full brunt of the storm.

We began our trek at the traditional starting point at 3,000 feet above sea level in the town of Besisahar, making our way up newly constructed dirt roads on top of the old trail. Most trekkers go counterclockwise around the circuit—the same direction cyclones rotate—because it's more gradual and facilitates better acclimatization. Up until 1950, walking presented the only way to enter or get around Nepal. Even today, traveling by road or air here is considered the most dangerous in the world. Many purists were afraid the circuit's four-wheel-drive roads would take away from the majesty of the trek. Vehicles were infrequent, as it turned out, mostly carrying tourists bent on finding shortcuts over the initial stretches, but the roads do provide a boon for locals and make it much easier to bring in fresh supplies.

Fees for entering the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP), similar to a national park, go toward education, infrastructure, and preserving the natural and cultural heritage. The 4,700-square-mile area in north-central Nepal draws 100,000 tourists per year, matching the number of permanent residents within its boundaries. And because of post-monsoon season festivals, there were delays in issuing ACAP passes, sending an unusually high number of trekkers heading for the high country.

We'd opted to carry our own gear instead of hiring porters. I had this primal fear of being separated from my survival tools, including our winter gear. Although the circuit is considered a tame trek, at least by Himalayan standards, I'd seen plenty of things go wrong in the Rocky Mountains.

We spent the first few days making our way up the Marsyangdi River Valley through sweltering terraced rice fields, punctuated by prismatic waterfalls, to reach the Himalayas proper. Pungent crops awaiting harvest reached for diffused sunlight. Yashoda pointed out millet, ginger, and rice growing along the roadside. Dust sopped our eyes as we passed a massive construction project, a hydroelectric plant, which will only modernize things further. The electrical system in Nepal is cobbled together and often fails, so you have to take what you can get. Sonia, having grown up in south Texas, was looking strong in the hot weather. At one point, she said, "I feel like I can trek forever." We'd trained that summer by hiking and camping in the Rockies and meticulously testing every piece of gear. For five to eight hours a day, she was carrying more than most of the male trekkers who seemed a tad provincial with their daypacks and columns of hired porters.

As we trekked along, we admired the heart-shaped leaves of

Bodhi trees, made famous by Buddha's meditations. Our tribe of

trekkers was sorting itself out, and faces were becoming

familiar in an ever-changing landscape. The circuit draws an

eclectic community, many of whom are going through life

transitions: career changes, spiritual quests, relationship

breakups. For us, we had some rare flexibility in our schedules

and wanted to experience the culture and see the big mountains

I'd read about in countless mountaineering sagas.

Some trekkers unplug entirely, while others put priority on Facebook and overwhelm village WiFi networks with photo file transfers. The toughness of the trail unleashes emotions, and experienced guides are not altogether surprised to see their much taller clients, mostly of European stock, explode into tears. And sometimes the calamities are more physical. When a client in another group was having trouble with her hiking boots, a 3 Sisters guide donated hers and walked for two days in her client's shower shoes. Young, fit Israelis, who catch the wanderlust after completing mandatory military service, were disproportionately represented and commonly trekking without guides. Whatever the motivation for being here, there's subtle pressure to move forward. Rooms at teahouses fill up, and solar-heated water goes fast, especially during October's high season.

The trail has a way of disarming trekkers by feeling a little too much like home. Signs and restaurant menus are in English. Shacks between villages answer Western sugar cravings by offering Coca-Cola and Snickers. One inn named itself The North Face and even borrowed the outdoor product company's official logo. Another was called Hotel Hilton Restaurant and Guest House. Adorable Nepali children offer the traditional namaste greeting in prayer pose. Those who are too young to talk just slap their hands together in fine clouds of dust. Knowing that tourists often pack chocolate, the children hold out their hands and chant "sweet, sweet." But at the same time, life continues for Nepalis trying to eke out a living. Everything is done by hand, mostly by women as the males are often doing construction, driving taxis, or working abroad. The trail kept us entertained with religious artifacts appearing in shadowy spaces and domesticated animals popping out in narrow quarters. In Danakyu, on the edge of the electrical grid, there was a chorten, a Buddhist shrine, in front of a waterfall to protect villagers from natural disasters.

We met a lodge owner there who, like many Nepalese, was still displaying a portrait of the royal family before they were murdered back in 2001. The woman's place was exceptionally well kept, and we admired her cooking. Out of the blue, she said that she'd love to come to America, describing it as a "dreamland," while tourists, meanwhile, trundled up the trail, trying to untangle confused lives. Some of them were from elsewhere in Nepal with the telltale dyed hair and skinny jeans of an urban hub like Kathmandu and were seeing these villages and mountain vistas for their first time. Although they spoke the national language, they were every bit as out of place as we were among the various subcultures. It was hard to believe that up until 2006, Nepal was in the midst of a civil war.

A few hours outside the village of Chame, Yashoda noticed the river turning from a steely gray to a deep black, a clear sign to her that rain was coming, the first bad weather we'd encountered. On came the rain gear, and it turned into a cold march. With wet gear hanging from our packs the next day, we were happy to have good weather again. Because a bridge was out farther up the trail, only motorcycles were making it beyond Chame. We noticed the food wasn't as fresh and the popular dish, dal baht, was getting blander without pickles or sharp-tasting delicacies like bamboo to give the rice, potatoes, and lentils an extra spark. Another sign, literally, that things were getting more rustic, was a billboard encouraging elder Nepalis to act more modern by using toilets instead of defecating in the woods. There also was a sign that helped offset the unpleasantness of the other: "Welcome to Manang District. The snow leopard is a symbol of Himalayan Grandeur."

Somewhere along the way, Sonia picked up bacteria and had a stomachache. Desperately weakened, it was miraculous she made it to the village of Manang in the afternoon. At 11,000 feet and about 56 miles into the trek, the Tibetan-influenced town represents a staging area for going higher, including the crux of the circuit, crossing the 17,769-foot Thorung La, one of the highest passes in the world. Manang has one main dirt street akin to an old Western town. There were cafes and two movie theaters, which were more like garages, featuring survival-oriented playlists like "Into the Wild," "Into Thin Air," and "Touching the Void." Guests would sit on fur-lined seats and were served tea and popcorn. At the other end of town, where the locals live, there was a maze of old stone buildings. Goats and yak-cow hybrids grazed freely in the foothills while stores sold anything tourists might need from sunscreen to trekking poles.

Our plan was to take a couple of days to acclimatize—although we came from high altitude in Colorado—and explore some local attractions, then begin the two-day segment to get over the pass. But with Sonia down, there wasn't much to do except wait for her to get better. She crawled into her mummy sleeping bag and was convinced she could fight off the stomach bug.

And Sonia wasn't the only one who was down. Yashoda found out that the lama at Bhraka Gompa, who usually blesses trekkers with a puja ceremony and wishes them a safe journey over the pass, was in Kathmandu seeking medical attention.

A Hell of Their Own

From Manang, the trail heads north through a series of

villages, including the yak pastures of Yak Kharka at 13,287

feet and the blue sheep grazing grounds of Thorung Phedi at

14,599 feet. Beyond that, there are two overnight stopping

points, Lower Camp and High Camp, to spread out the hard slog

over the pass.

In the late afternoon of the day before the storm, 21-year-old Erin Erb, of Seattle, and her Israeli boyfriend, Tomer Cohen, 25, arrived at High Camp. They felt lucky to find beds and wouldn't have to resort to sleeping on the floor. They shared a sleeping bag. Packed with 200 people, the teahouse was unusually crowded, even for high season. They were trekking with two friends of theirs, an Israeli couple who'd hired a porter.

Although Erb didn't have much outdoor experience—other than day hiking and car camping—a week before the Annapurna Circuit she and Cohen had completed the Mount Everest Base Camp trek, which reaches a slightly higher altitude. Unlike the Annapurna Circuit, though, their Everest trek was uneventful.

On the morning of the storm, Jim Schaden, 68, and his wife Jeanie, 66, of Rockland, Maine, rose at 3:30 a.m. at the similarly crowded Lower Camp. After a hot breakfast, they and their experienced guide and porter were out the door by 4 a.m. Dressed in warm clothing, the couple figured they were among the oldest on the trail and were a good hour and a half behind those leaving High Camp. A narrow, steep path connects the camps, and the snow was just beginning. Soon the Schadens found themselves in the middle of a line of 300 to 400 trekkers, headlamps blazing, making the steady high-altitude shuffle. Jim Schaden was hoping the snow would stop on the drier, western side of the pass. Like almost everyone else, the couple hadn't heard about the cyclone and assumed it was simply a smaller squall.

Avid hikers, the Schadens had experience to draw on. Four years ago they completed the Everest Base Camp trek with the same guide. They'd also climbed 19,341-foot Kilimanjaro in Africa and lived in Alaska for nine years. They figured their best shot was to keep moving and traverse the pass while daylight remained. With limited visibility and slippery footing, it was too dangerous to turn around and walk against the upward moving herd. They were shocked by how unprepared the other trekkers were, some of whom were experiencing snow for the first time.

Like Lower Camp, the teahouse at High Camp stirred to life in the early morning hours. Erb and Cohen awakened at 5 a.m. to find a foot of snow on the ground. They were among the last to leave at 6 a.m., presumably somewhere behind the Schadens. Erb remembered an "enormous train of people" who were laughing and in good spirits. As in Manang, the fresh snow was a novelty.

Erb's group, like most of the other trekkers, had merely summer gear. They put on their sunglasses to block blowing snow. Even before the storm, Erb and Cohen were concerned that their friends' porter was ill-equipped, although he'd been over the pass before. In a village somewhere along the way, they'd bought him what was available, a women's canvas jacket. It was far from adequate.

As they trudged along, they became more concerned about the conditions. Their friends were motivated by thoughts of relaxing by the lake at Pokhara as their vacation time dwindled. Since the group opted out of doing the full circuit, their finish line was just over the pass in Jomsom where they could catch a jeep and proceed south down the horseshoe's other arm. At around 8 or 9 a.m., Erb and Cohen decided the conditions were only getting worse and, against pressure from the struggling herd, turned back while the Israeli couple decided to keep going.

Erb and Cohen said their goodbyes and gave the other couple a

chocolate bar they'd been saving as a surprise. On the way back

down to High Camp, Erb realized just how serious it was. The

trail had filled in with fast-falling snow, and because of the

flat light, they couldn't see drop-offs. Cohen bravely took the

lead and told Erb to walk only in his footprints. They were now

alone and it donned on Erb that it was, in fact, a

life-threatening ordeal.

They made it back to High Camp and found 15 to 20 other people,

all soaking wet. Of the 200 who headed up, only eight had

retreated. The rest of the people had come up from Lower Camp

and stopped.

Erb's friends, meanwhile, made it to the last shelter before crossing the pass. Backpacks were stacked outside to make more room. Conditions were deteriorating on the inside as well. People were going to the bathroom on the floor in front of each other rather than heading back out in the blizzard.

At some point, the proprietor decided to evacuate and offered to lead the trekkers over the pass for $2,000, which worked out to $20 apiece. Seeming like a good enough deal, a group of trekkers, including the Israeli couple, followed the man on horseback. Every step was a struggle in the hip-deep snow.

They walked until dark in summer hiking boots. They saw at least two dead bodies. Somewhere below the pass, the couple was too weak to make it any farther. Their porter waited for several minutes, then disappeared. He was later found dead.

The Schadens, meanwhile, only stopped for a few minutes every

two hours. Although they'd started in the middle of the pack,

they were now in the front. The storm had picked up in ferocity,

bringing higher winds and heavier snow as they neared the pass.

An array of emotions leered from whiteout conditions. Some

trekkers decided to wait out the storm on the pass while others

were either paralyzed by fear or too exhausted to move and sat

on snow banks and cried. The Schadens told other trekkers that

they had an experienced guide and implored them to follow.

If the east side of the pass was rough, the west side was treacherous. It was sheer ice and people, including the Schadens, fell repeatedly. They, nonetheless, kept moving. Once they made it to the bottom, Jim Schaden turned around and asked, "Where is everybody?" They were alone.

What would have normally taken seven or eight hours had turned into twelve. The Schadens made it to the nearest town, Muktinath, at an elevation of 12,335 feet. The power was out and they huddled by a fire. During the evening, a horrific avalanche let loose and killed an estimated seven people who were trying to make their way down the pass in the Schadens' now invisible footsteps.

"I never felt like we were going to die there. We kept going," Jim Schaden said.

Still caught in a communications black hole, the Schadens wouldn't be able to reach their only child, a son in New York, for four days. In any case, Erb and Cohen—who were poorly equipped for the conditions but much younger—and the Schadens—who were much better off but older—had made the right decisions and won their respective coin tosses.