Originally appeared in Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine.

The Peden family has given up seeing sunsets. Ed Peden, an ultralight manufacturer, and Dianna Ricke-Peden, a speech therapist, live on Atlas E missile base No. 6, just southwest of Topeka, Kansas, and their home lies beneath three feet of earth. The section they use as a garage once housed a thermonuclear missile capable of flying 6,000 miles away and producing a four-megaton explosion.

Today, there are at least 15 decommissioned Atlas missile sites for sale, ready for transformation. Mark Hannifin of Midland, Texas, bought one that was flooded with 130 feet of water; he uses it for giving scuba diving lessons. About an hour from the Pedens' home, a missile base north of the town of Holton has been converted into a public high school. The entrance tunnel, which once connected the missile's launch area with its control center, has been painted red, white, and blue by the Jackson Heights High School student council.

Atlas missiles were America's first intercontinental ballistic weapons; 100 were installed in permanent sites around the country during the 1950s and early '60s, mostly in the Midwest. The Pedens' is one of 21 that went up in Kansas, which was happy to get the accompanying infusion of money. A 1958 story in The Topeka Capital was headlined: "Missile Base Is Viewed With Joy"; another, in a 1961 edition of The Kansas City Star, began: "What is happening in Kansas is almost incredible, and so awesome it shakes you right down to your boots. In a matter of a few months, Kansas will be the nation's No. 1 springboard for long-range missiles."

The Atlases were decommissioned only four years later when they were replaced by Titan IIs and Minutemen. In the years following, the Atlas sites were dispersed among local governments, companies, and individuals by the federal government's General Services Administration. Realty specialist John Robinson of the GSA's Ft. Worth, Texas, office says he gets hundreds of calls every year from prospective missile base purchasers (though the GSA no longer has any Atlas sites for sale, it does have sites once occupied by second-generation missiles). "Most want them for secure storage, and paranoid people want bomb shelters," he says. "Others want to grow mushrooms."

At least one other Atlas site has been transformed into a home, but that silo owner guards his privacy assiduously. The Pedens, on the other hand, are happy to share their story.

Back in the early 1980s, Ed Peden, then a teacher of history and psychology in the Topeka public school system, began to hear talk of Atlas sites in the area. He got his first look at missile base No. 6 in 1982; when he went to inspect it, the underground portions were flooded, and he had to conduct his tour with a canoe and a flashlight. But he saw the possibilities, so he paid a scrap dealer $40,000 for the property. It was a good deal: He got a 33-acre site with a landing strip, plus 15,000 square feet of available underground space. The ceilings were so high he was able to put in an upper level that added 3,000 square feet. Ed had long been interested in underground housing because, according to his advocates, it requires less energy to heat and cool. And he was able to use part of the launch area for assembling the ultralight aircraft he sells.

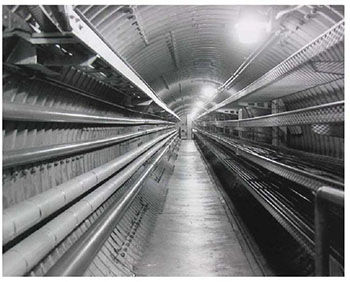

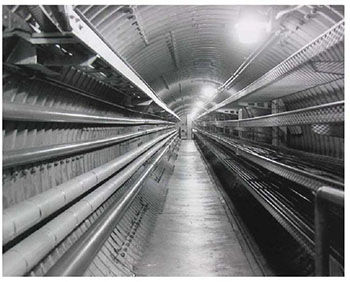

Today, two years after they finally moved in, the home portion looks fairly conventional, though a few structural inconveniences remain. It takes the Pedens several minutes to answer the doorbell, for example, as they have to walk the length of a 120-foot tunnel. The tunnel makes an eerie foyer. When the double steel doors at the end are slammed, they send dungeon-like echoes off the walls, as if you are entering another world or a really big basement. At the other end, a wooden door opens onto the former control center, now the Pedens' home. At 2,800 square feet, it's about the size of a typical suburban rambler. The inside seems unremarkable, except that the rooms have 15-foot ceilings and at the entrance to the living quarters is an old panel with switches for initiating a launch.